Say This, Not That

article

Say This, Not That

Say This, Not That

During an election, accuracy matters. Too often, we are prone to sacrificing nuance for the sake of brevity or a deadline. We put together this resource to highlight simple changes to wording or coverage approaches that can have a big impact. Below each suggestion, you will also find real-world examples of journalists and newsrooms using this type of specificity and nuance in their own work.

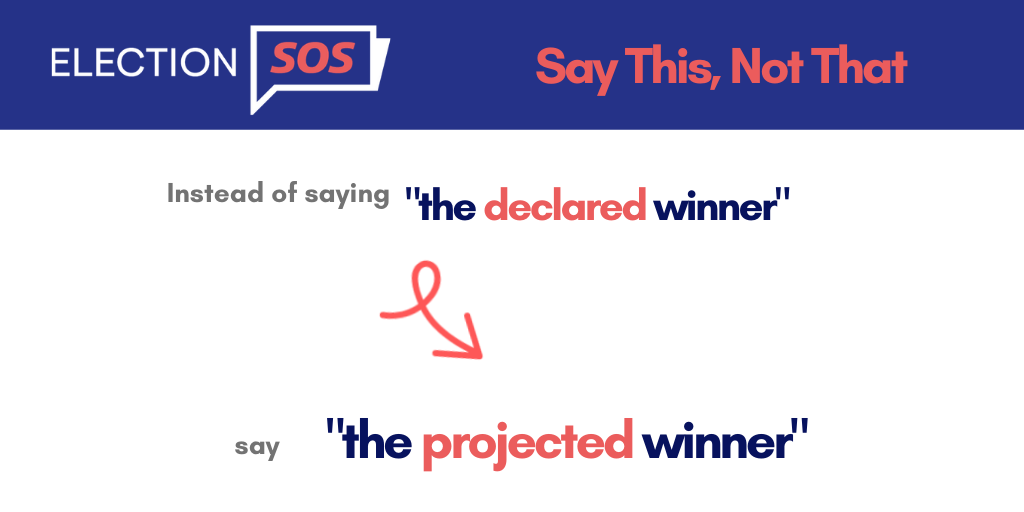

Some news outlets are already calling races, and, as a result, they are saying that certain candidates have won certain races. Remember that until the results of a race are certified, we can only speak of projected winners. This is especially important in the Presidential race. The results of that race will not be certified until all votes are counted and all internal disputes within each state are resolved. The deadlines for those events are December 8th (for internal disputes) and December 14th (for certifying results). Failing to speak about any “winners” in more flexible terms prior to those deadlines can mislead the electorate.

By framing the election as a process that ends as soon as all votes are cast, one situates a crucial part of the process—counting and certifying the votes—as outside of the process. This could not be more false. As we have shown, throughout these dates, the election is ongoing. Journalists should constantly remind readers that the election continues until the transfer of power (i.e., the inauguration in January). By doing so, they can counter the mis- and disinformation that seeks to delegitimize anything and everything that happens after votes are cast.

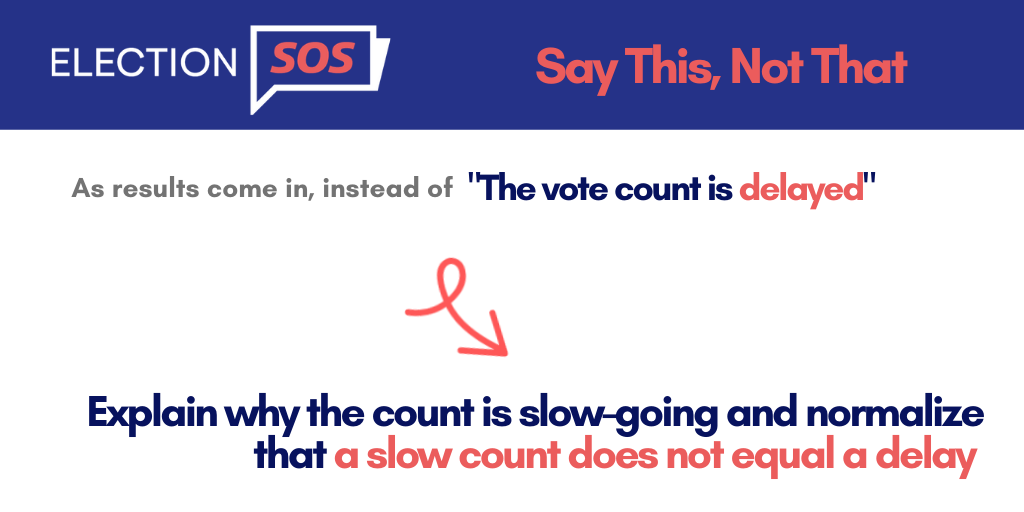

Delay typically carries negative connotations and implies that something in the process is not working as intended. This year, however, as most outlets report, the vote count may be significantly slower than the American public and media organizations are used to due to the increase in absentee voting. This article in the Wall Street Journal clearly outlines which factors may cause the slowdown, going so far as to explain that “counting mail ballots can take longer than in-person votes for several reasons, such as the time it takes to open return envelopes or verify signatures, depending on what a state’s law requires.”

Journalists should take care to frame these slowdowns not as delays indicative of a problem, but rather of a slower process that helps to ensure accuracy.

Experts in conflict mediation and de-escalation strongly discourage the use of metaphoric military terms like “battleground” that have a violent connotation. Instead, they urge journalists and the public to use terms like “competitive states” or “contested states” that are descriptive and emotion-neutral like in this 3News Corpus Christi story. Similarly, avoid phrases like “battle for the White House” which imply a civil war.

As expert and former acting assistant attorney general for national security Mary McCord writes in the New York Times, these private armed groups have no constitutional or statutory right to exist. Regardless of the political affiliations of such paramilitary organizations, journalists should take care to consistently underscore their illegality or use neutral descriptors like “self-organized armed groups” to de-escalate violence. Further, journalists should also avoid calling these militias by name, since experts have observed spikes in recruitment by these militias after being named in the press.

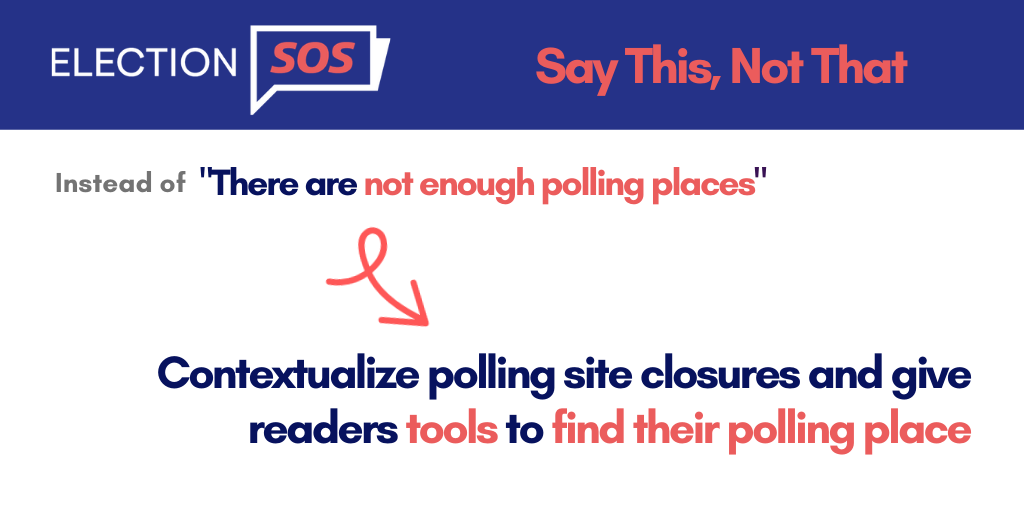

An article in The Atlantic written by two election law experts exemplifies this with a paragraph like this:

“As the pandemic has unfolded, an expansion of mail balloting has become the central focus of reformers, state lawmakers, and the litigants in voting-rights cases. But Americans will most likely still go to the polls on Election Day, and many of them will go to polling places that are unready to receive them.”

The article then covers specific challenges to in-person voting, all while explaining other threats to voting by mail.

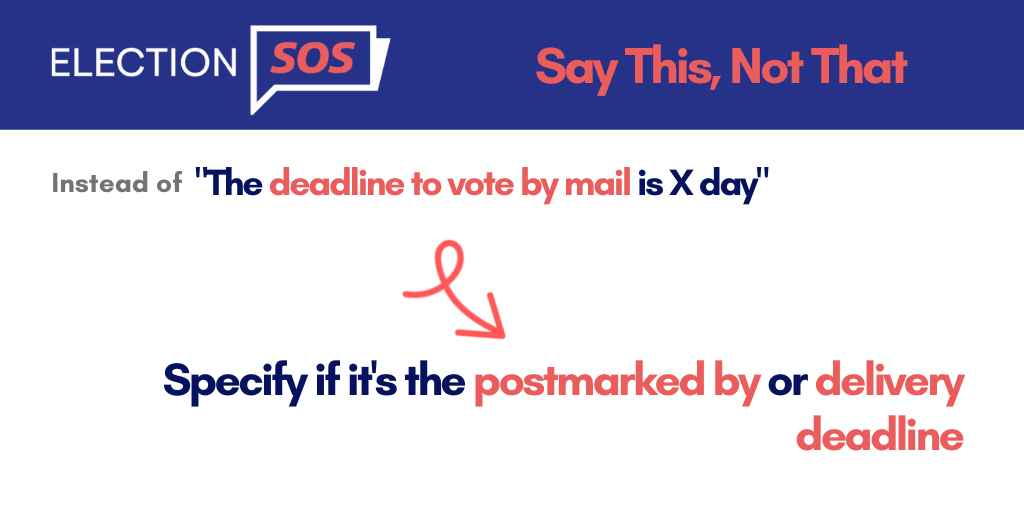

The Washington Post created a comprehensive and user-friendly tool for voters in every state to find how to vote either by mail or in person. Importantly, they not only provide the official dates, but they also include warnings such as: “The U.S. Postal Service recommends voters mail their ballot at least one week prior to the state deadline, by Oct. 27.” The Post’s tool nods to the complex dynamics between federal organizations and state elections boards without overwhelming the reader.

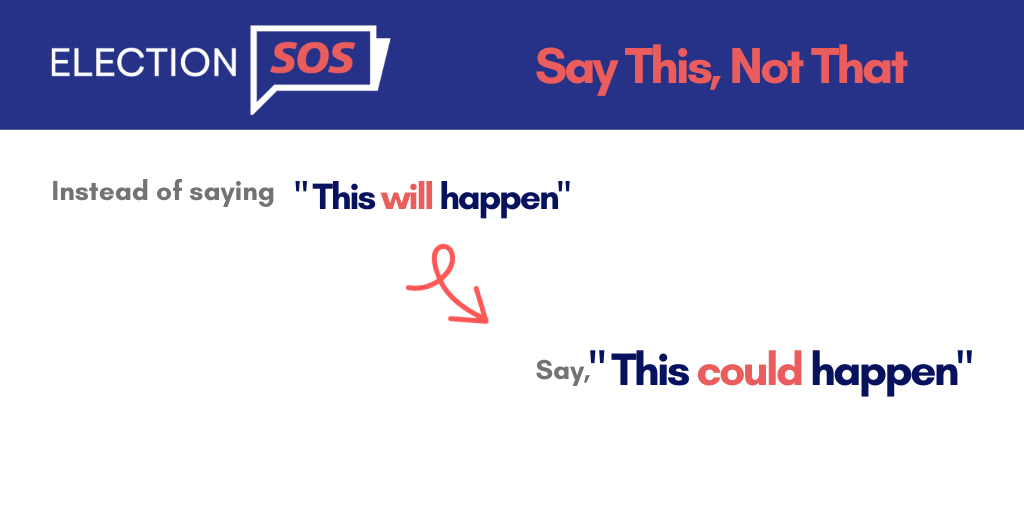

Many responsible news outlets are already doing a great job at using “could” instead of “will” to describe potential outcomes. As newsrooms learned from the 2016 election, using the language of certainty to describe what might happen only exacerbates the public’s confusion when the opposite turns out to be true.

For example, The Economist recently published an article on what a contested election could mean, saying that “there is a real risk that things could go wrong in November.” Unfortunately, however, the author of this piece then reverts to the formula of “if abc were to happen, then xyz will happen,” instead of continuing to use could to show the level of uncertainty.

This recommendation comes from a guide for journalists by our partner, the American Press Institute. It cites as a positive example an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, where journalist Jonathan Lai explains that “elections officials in Philadelphia have faced a number of challenges pulling off primary elections during the coronavirus pandemic, including unprecedented shortages of poll workers. Finding suitable polling places has also been difficult […] because they need to be able to accommodate large numbers of voters who are spread out for social distancing.” Lai also embedded a tool allowing readers to find their polling place directly via the article.

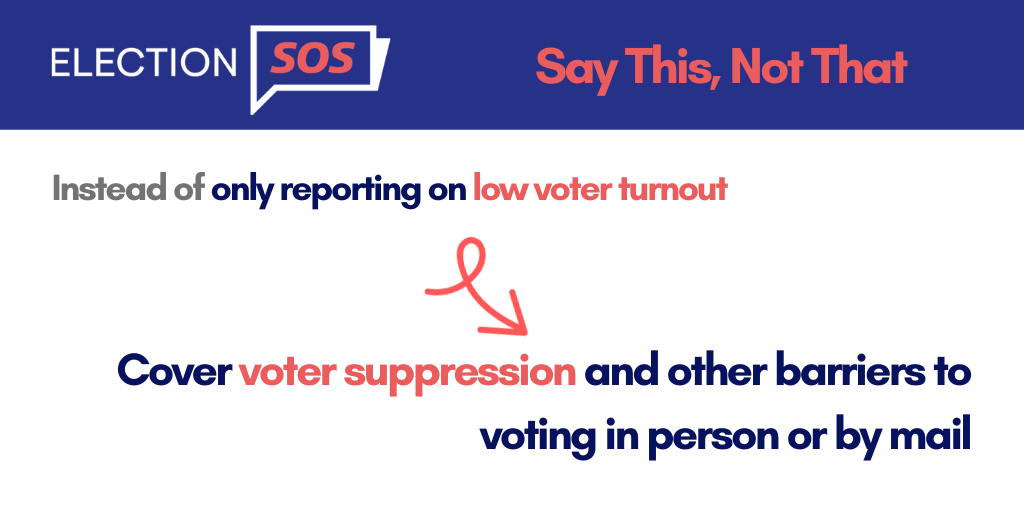

In 2018, the Washington Post published an analysis of the correlation between the ease of voting and the turnout in each state. The results may not be surprising: when states made voting more accessible, turnout increased.

The 2018 midterms elections saw a rise in projected turnout, especially in Texas, a state where turnout is notoriously low. As Pew reports in this article, “critics say a voter ID requirement, which went into effect in 2013 and has survived years of legal challenges, also has played a role” in low voter turnout.